I have not been to the local Day Of The Dead ceremonies the last couple of years.

This year we went to nearby- Ixlahuacan where the flavor was a bit different from what I have seen in our town in past years.

The main Plaza was transformed into a grave yard with sites commemorating deceased loved ones.

A little model of the town cemetery was also in the Plaza.

There was a competition going on for the best Catrina.

This icon has not always been a fixture of Mexican culture.

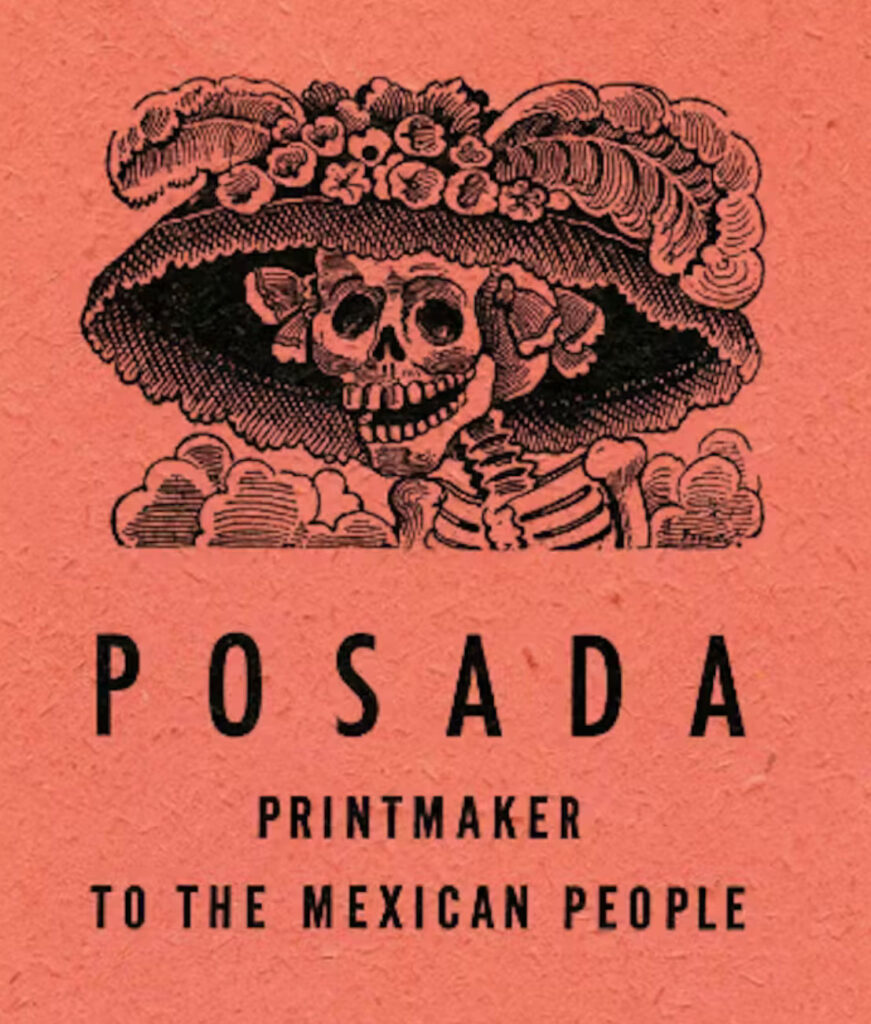

In 1944 thousands of people clashed with police on the steps of the Art Institute of Chicago. A massive, impatient art crowd overwhelmed the museum’s capacity. That’s how desperately people wanted to see the U.S. premiere of an exhibition titled “Posada: Printmaker to the Mexican People” featuring the prints of José Guadalupe Posada, a Mexican engraver who had died in 1913. On display were his calaveras, the satirical skull and skeleton illustrations he made for Day of the Dead, which he printed on cheap, single-sheet newspapers known as broadsides.

Known as La Catrina, she was a garish skeleton with a wide, toothy grin and an oversized feathered hat.Back in Mexico she’d been virtually unknown, but the U.S. exhibition made La Catrina an international sensation.

Posada illustrated her in ostentatious attire to satirize the way the garbanceras attempted to pass as upper-class by powdering their faces and wearing fashionable French attire. So even from the beginning, La Catrina was transcultural – a rural indigenous woman adopting European customs to survive in Mexico’s urban, mixed-race society.

In 1947, Diego Rivera further immortalized La Catrina when he made her the focal point of one of his most famous murals, “Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Park.”

The mural portrays Mexican history from the Spanish conquest to the Mexican Revolution. La Catrina stands at the literal center of this history, where Rivera painted her holding hands with Posada on one side and a boyhood version of himself on the other.

Below are just some of the many competitors, young and old, official and unofficial.

On a side street many altars and colored sand and flower paintings.

The altars were all dedicated to particular loved one.

Above. These were all campesenos or farm workers.

The altars all had a wash basin and mirror so that the returning spirits could see themselves.

“Only the forgotten are dead”